It was a true blessing to journey with the Cardus NextGEN Fellowship over the past year. Our cohort’s final weekend together in Halifax was bittersweet, but a great conclusion to a year of community, learning, and encouragement in the Lord.

For the final conference, each of the Fellows was asked to give a short presentation answering these questions:

“What is your vision for your vocation?

How would you articulate to others where and how you are being called to use your gifts in God’s service? What challenges do you want to take up? What changes in your sphere of influence or in the world do you want to see?”

Also, select a brief reading you would like to share with the other Fellows that relates to your vision for your vocation. It can be an article, video, or other resource… Something to get us thinking and talking with you about what you care about.”

Below are the “answers” I have (so far!) to these rich questions, and I am excited to see how God will illuminate the path He has for me.

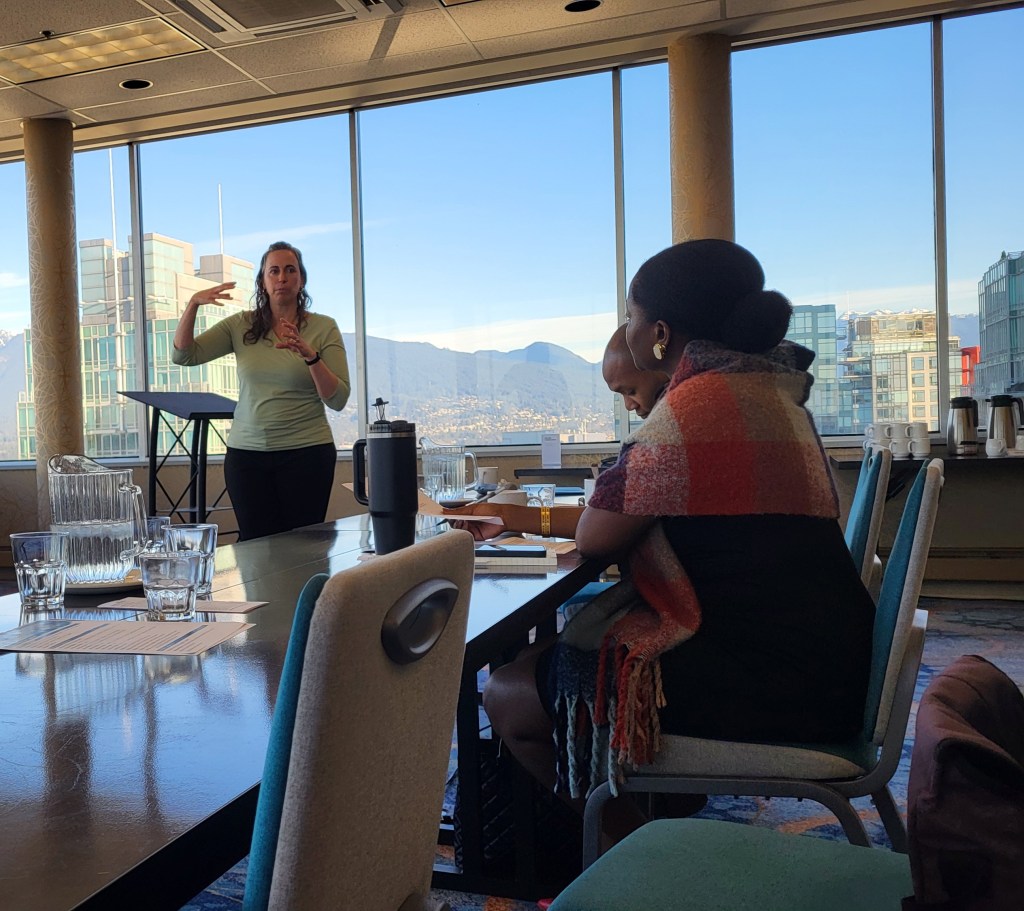

Back in January, our Fellowship met for a (surprisingly sunny) weekend in Vancouver. During one of our sessions, Biblical scholar Dr. Mariam Kovalishyn spoke on the wisdom contained in the letter of St. James. One theme she highlighted in the letter was the danger that can come with the unbridled pursuit of our desires. I asked her a question I’ve been wrestling with, about the tension I see in Christianity when it comes to our desires.

On the one hand, there’s the common message that our desires are the things that most easily lead us astray from God, because we make idols out of them so easily. But on the other hand, there’s also the message that God speaks to us in our desires, and that He is really at the root of them. Even a disordered desire presupposes a rightly-ordered desire which is, at bottom, the desire for God. “These messages seem like contradictions,” I said to her. “How do we reconcile them?”

And I loved her answer.

She first affirmed that, yes, pursuing what we want blindly–without surrender and discernment–can easily lead us to all sorts of idolatry. But then, she pointed to the story of St. Peter. When Our Lord called St. Peter, Christ didn’t say to him, “Follow me, and I will make you a…theologian.” Or “a teacher,” or “a healer.” He did make him all of those things, but He called him to be a “fisher of men”. After all, who was Peter? A core aspect of his identity was that he was a fisherman. Dr. Kovalishyn said, “Fishing was the one thing Peter knew how to do, and the one thing he’d do when he didn’t know what else to do.” God knew that about him because He created him. God shaped his heart in that particular way, and then called him to use his desires and gifts for His glory.

The same is true for me: God wants me to make a gift of my life for His glory, including through my (sanctified) desires.

So, I’d like to look back on my life and ask the question, “What did I do when I didn’t know what else to do?” Because the truth is that I have known many a rock bottom, where I had no idea what to do. And instinctively, in my better moments, I gravitated towards at least two things: justice-oriented work to try to help the vulnerable, and scholarly work in contemplation of the beautiful.

To put it bluntly, I volunteered, and I read poetry or listened to lectures.

Justice-oriented work, practical service to neighbour, matters greatly to me—and so do the Humanities. It’s no secret that the Humanities are massively impractical, though. I’ve wrestled with justifying time in that sphere when there are so many areas of pressing human need. And I’ve wrestled with how to understand the question of vocation at all in the complicated context of a life with chronic illness.

These questions found a surprising meeting-point in C.S. Lewis’ 1939 sermon, “Learning in War Time,” and I asked the Fellows to read it in preparation. In this sermon, Lewis addresses a group of Oxford students and knows that they likely also question the value of their intellectual work while living in a world at war. And they wonder, practically, how to pursue their callings in the midst of deep social upheaval. As I consider my own vocation, I will draw on three themes from his sermon that grip me:

- The call to justice-oriented work;

- The call to cultivate beauty, especially through the Humanities; and,

- The reality of uncertainty, and the practical skills and spiritual aid needed to face it.

Justice-Oriented Work

So often in prayer I have asked, “Lord, what am I supposed to do? What do You want me to do with this day, with this week, with my life?” I am then reminded, however, that God has said so much in His Word about how He wants me to live.

Micah 6:8 comes back over and over. “He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God?”

And throughout Scripture, He shares His heart for the weak and the marginalized. Proverbs 31:8-9 says, “Open your mouth for the mute, for the rights of all who are destitute…defend the rights of the poor and needy.”

I am called to love my neighbours, and especially to care for my neighbours who are vulnerable or voiceless. This calling obviously extends to many areas, but it’s been particularly important for me through work in the pro-life movement. No one is more vulnerable than a pre-born child. No one is more voiceless. The tragedy of abortion has weighed on my heart for years, and I’ve long known that the pre-born are a group of neighbours I have to speak for.

To get more specific about where and how I think I’m called to serve in the pro-life movement, I prioritize work as a communicator and as a peacemaker.

Communications

Communications work is the area I’ve served the longest in the pro-life movement and have already elaborated on elsewhere. I will say that practically, I want to improve in communicating using simpler, more understandable language. “Less jargon” and “more story-telling” are big goals for me. Whether in presentations or in other advocacy, I want to speak in a way that’s accessible and persuasive.

Peace-Maker

Something that has increasingly mattered to me over the course of the Fellowship is being a peacemaker. The pro-life movement, like other social justice movements, is full of passionate people with strong opinions. (Not that that would describe me in the slightest.) One common problem, though, is the reality of disagreements—whether over mission or strategy, over religious or philosophical views, etc.

I’ve seen two common approaches to navigating those deep differences. One common strategy is that of peacekeeping (or what I sometimes think of as the “Kumbaya approach”). Some will avoid conflict by saying, “Well, our job is simply to be faithful without worrying about results. Therefore, we will not criticize any approach that anyone takes because God will always bring good out of it.” I think that response is fundamentally flawed (and not a good representation of Divine Providence). In order to engage in critical thinking about strategy and vision, we have to be willing to criticize when necessary, and recognize that not all approaches will work equally well in every context. And effectiveness matters if the goal is saving children’s lives and fostering cultural change.

Nevertheless, I sympathize with the people who adopt the “Kumbaya” approach, because they’re often trying to avoid the other end of the spectrum: criticism that devolves into contempt, and sometimes leads to toxic infighting.

When Elizabeth Oldfield spoke to our Fellowship in July 2024, she said something that’s been rattling around my brain for months. She said, “Contempt is poisonous. If you notice contempt creeping in, go and fall to your knees.”

I already knew about the dangers of cynicism creeping in, but I had not considered the dangers of “criticism-for-actions” gradually souring into not just frustration, but contempt for persons.

I want to learn how to walk the virtuous middle path. That means refusing to take the “peacekeeping” approach, which shuts down critical analysis and thwarts growth. Crucially, though, I also must reject the path of contempt. It leads to an ever-shrinking circle of people I’m willing to work with, and an ever-tightening vise around my heart.

I want to learn from Christ how to be a peacemaker. That involves resolutely facing conflict, and resolutely refusing to dehumanize anyone involved. But I can’t cultivate peace in pro-life spheres unless Christ cultivates it in my heart. He leads me beside still waters, He restores my soul. And one of the ways He does so is through encounters with Beauty.

Beauty-Oriented Work & the Humanities

Responding to injustice isn’t all that Christ asks of me, or of you.

In Philippians 4:8, He instructs us through St. Paul, “Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things.”

That brings me to another aspect of my vocation that has become clearer to me over my time in NextGEN. (It shouldn’t have surprised me, but it did, because I couldn’t see the forest for the trees.) I want to cultivate Beauty through the Humanities, especially through literature and philosophy.

As I’ve mentioned, I’ve sometimes felt a tension between my interest in the Humanities vs. the necessity and urgency I see for pro-life work. As Lewis asks, in the middle of a crisis, aren’t scholarly pursuits a frivolity—”like fiddling while Rome burns?” He addresses this question head-on, in a practical and helpful way. He first points out a key truth: that we are always in a world at war. We’re always living in times of crisis and catastrophe. We can’t wait until peacetime to pursue Goodness, Truth, and Beauty. We have to start now.

He also highlights the very practical reality that everyone will engage in cultural activities in one way or another. The question is, will I pursue God-honouring ones that promote my flourishing, or ones that work in the opposite direction?

Lewis says, “You are not, in fact, going to read nothing, either in the Church or in the [military] line: if you don’t read good books, you will read bad ones. If you don’t go on thinking rationally, you will think irrationally. If you reject aesthetic satisfactions, you will fall into sensual satisfactions. There is therefore this analogy between the claims of our religion and the claims of the war: neither of them, for most of us, will simply cancel or remove from the slate the merely human life which we were leading before we entered them.”

Fair point, Jack. Surely spending some time reading poetry will be better for me than doomscrolling on my phone.

I want to, by God’s grace, endure in work in the pro-life movement. I’ve realized that immersion in the Humanities will actually help sustain me in that work, rather than “distracting” me from it. In order to endure more difficult times, I’ll need to be nourished by beauty.

There’s a level even more fundamental than that, though, in the value of the Humanities. I don’t think that any beauty should be valued merely for the instrumental end of “helping Maria’s mental health,” though it certainly does that. Beauty’s value lies even deeper.

I was fascinated by a session our cohort had with Dr. Amy Sherman, where she spoke about two aspects of our vocations. Some aspects of our lives, she noted, will be restorative, i.e. responding to the reality of a post-Fall world. Disciples are all called to co-labour with Christ in repairing and restoring what is broken.

She also pointed out, though, the importance of generative work that offers, in her words, “a foretaste of Kingdom goodness.”

A foretaste of Kingdom goodness.

Responding to darkness and brokenness is the reality of a post-Fall world. But in the beginning, it was not so. And in the end, it will not be so. We were called to work in Eden before there was any brokenness to restore. And we will one day live in the new creation, where God has wiped away every tear and swallowed up death forever. Our vocations necessarily extend beyond the restorative.

I realized that I must contemplate beauty (and truth, and goodness), not merely as an antidote to darkness, but as a foretaste of kingdom goodness. The darkness is ultimately an aberration. The goodness is that which is fundamental.

In 2024, I attended a 150th birthday party for G.K. Chesterton (and it may remain the greatest day of my life.) At the party, I was gifted a copy of a quote by him. It now hangs in my room.

I find it hard to read his words aloud without choking up:

“There is at the back of all our lives an abyss of light, more blinding and unfathomable than any abyss of darkness; and it is the abyss of actuality, of existence, of the fact that things truly are, and that we ourselves are incredibly and sometimes almost incredulously real…

He who has realized this reality knows that it does outweigh, literally to infinity, all lesser regrets or fears of negation, and that under all our grumblings there is a subconscious substance of gratitude.”

The goodness, my friends, is what is fundamental. The darkness is a passing shadow. The Light endures.

Honestly, there’s a big “question mark” in how I should move forward in the Humanities. My chronic pain affects my wrists and hands acutely, which makes the writing process tricky. I’ve gotten better at using voice-to-text, but it’s still extremely difficult to dictate rather than write. (Though it does give me the fun opportunity to call myself a dictator.)

I do know that there are at least four writers whom I want to focus on and read more deeply:

- T.S. Eliot, a Modernist poet whose work has haunted me since I was a teenager;

- G.K. Chesterton, the English Catholic writer whom I’ve already gushed about;

- Dr. Viktor Frankl, a Jewish-Austrian psychologist who survived the Holocaust and wrote the landmark book Man’s Search for Meaning; and,

- Pope St. John Paul II, whom we studied a bit in the Fellowship.

As a concrete next step, I plan to apply for the Lumen Gentium Forum in Toronto. It’s a program for Catholic young professionals and includes deeper reading in Catholic Social teaching. I think it’ll be especially helpful for learning more about John Paul II’s work.

Clearly, I’ll have lots of reading to do. Writing will have to happen slowly and within limitations, and I am learning to make peace with that.

The Reality of Uncertainty

Because living with chronic illness means that I live with great uncertainty. I never know for sure what my body will be able to do on a given day, let alone 5 years from now. In some ways I felt frustrated by the question, “What is your vision for your vocation?” It felt like a “luxury question” for someone with a certain level of health and wealth. But I know that the call to holiness is for everyone, and it is anti-Gospel to view illness or finances as a barrier to holiness. I also know that closing myself off to life’s possibilities won’t prevent disappointment. It will simply guarantee failure.

And of course, I don’t have the market cornered on uncertainty—it’s a reality of the human condition. As Lewis points out, we are always in a world at war. I think back to this time in March, 5 years ago. I suspect that for each person reading this, certain life plans changed on a dime as we plunged into a global pandemic and came face-to-face with our lack of control.

One practical approach that helps me in living with uncertainty is a concept I learned in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: the difference between a value and a goal.

One online definition I found stated, “Values are beliefs that guide your actions, while goals are the specific steps you take to achieve your values.”

I would word that slightly differently, and say that goals are ways of embodying a value. So, for instance, someone who really values “adventure” may have goals like “attending a local rock-climbing class” or “doing a backpacking trip across Asia,” and the goals will have to be suitable to her circumstances in a given season.

I can’t always choose my circumstances. But I can choose to live out my values—to pursue justice and cultivate beauty—regardless of my circumstances. I can focus on embodying these values, knowing and expecting that the concrete goals will change from one season to the next.

Finally, facing uncertainty also requires the spiritual help of remembering the bigger picture. The purpose of my life isn’t merely “meeting certain goals” I set. The purpose of my life is holiness. Holiness comes from communion: from a loving union with God that spills outward into love for my neighbours. As St. John of the Cross said, “In the twilight of life, we shall be judged on love alone.”

God enables deeper love at every moment of my existence, not in spite of my limitations, but precisely through my individual circumstances. That’s also an important reminder that so many other aspects of my life—such as helping care for my younger brother, or exercising, or doing laundry—those aren’t “distractions” from more important parts of life. They’re equally important. Those are the very circumstances where I can give love and receive love.

And so, my vision for my vocation at this particular moment in time:

I desire to seek justice and mercy, especially for pre-born children who often receive neither. I desire to cultivate beauty, especially through the Humanities. And in all of that, I walk in daily uncertainty. But the not-knowing is an invitation to trust in the Lord, rather than leaning on my own understanding.

If you are a Christian young professional looking for formation and community, I highly recommend applying for the next cohort of the NextGEN Fellowship! Apply by April 30th: https://www.nextgenfellowship.ca/