-

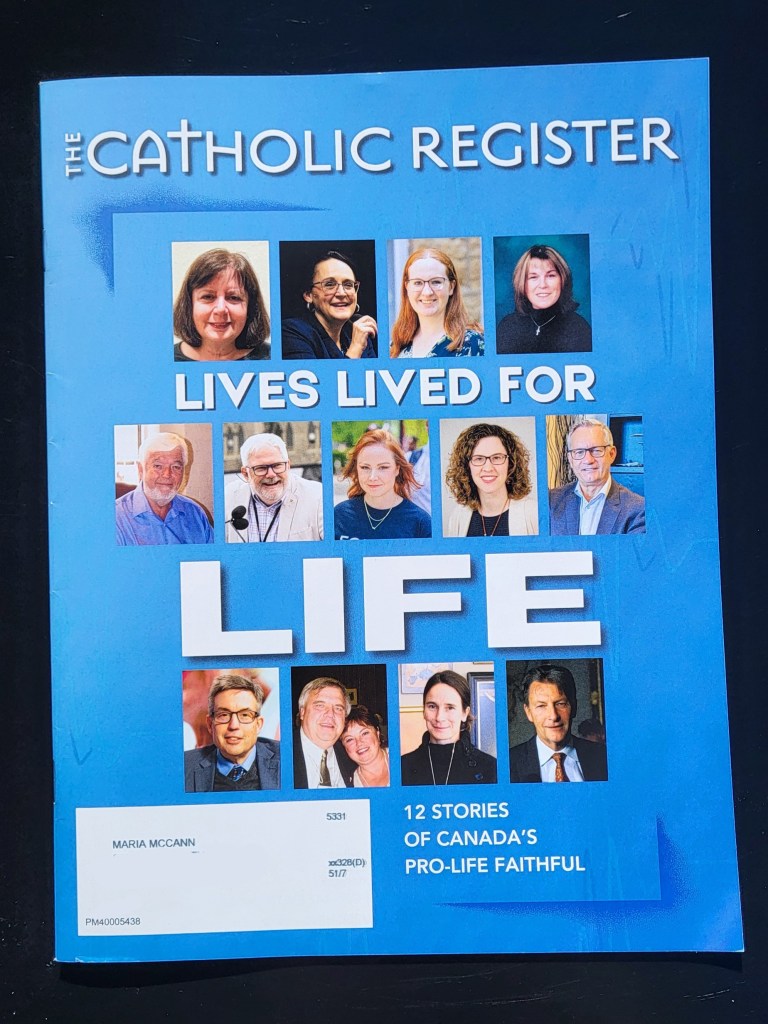

“Lives Lived For Life” Magazine

Earlier this year, I was interviewed by the Catholic Register about my involvement in the pro-life movement. I was overwhelmed and humbled to be included in their “Lives Lived For Life” issue, a special edition which highlighted 12 stories of pro-life Canadians.

My prayer is that anyone who reads the issue realizes that every one of us has a role to play in ending abortion. The pro-life movement is not about me or about you. It’s about our pre-born neighbours, little girls and boys, whom God calls us to protect from slaughter.

Get Involved: EndTheKilling.ca/TakeAction

I’m so grateful for the support of my family in doing this work, and for the countless pro-life colleagues who’ve become a second family.

Soli Deo honor et gloria!

-

Quo Vadimus?

I wrote the following short essay as part of my application to the Cardus NextGEN Fellowship, which I’m excited to take part in. The application question asked, “Do you think religion can play a role to promote greater flourishing in modern democratic societies? If not, why not? If so, what do you think are the biggest barriers or challenges to that today?”

Truth. Goodness. Beauty. Western philosophy and religion often focus on these three great “Transcendentals”. As I contemplated the question of religion’s role in social flourishing, the transcendentals immediately sprang to mind. (I will speak primarily about Christianity’s role in modern society, because my knowledge of the transcendentals in other traditions is limited.) Christianity and other major religions obviously strive to serve the Good, especially by helping marginalized or suffering people. And while many might deride Christianity’s views of the Truth, there can be no doubt that Christianity contends with the Truth and tries to promote it in modern society. Yet, Christianity faces obstacles to its promotion of Truth and Goodness, and these obstacles hinder its ability to promote social flourishing.

Two pervasive ideologies, in particular, act as obstacles: materialism, which subverts the Good, and postmodernism, which subverts the True. One path forward for Christianity to break her “deadlock” with these two forces is the “via pulchritudinis”, the way of Beauty. Christianity can promote social flourishing by being a passionate cultivator of Beauty.

Both ends of the traditional “political spectrum” are short-sighted in their goals for human flourishing. Too often, they limit their focus to only the material Good. Whether we think of left-wing politics that advocates for redistribution of property to end poverty, or right-wing politics that wants to expand production and employment in order to build economic wealth, modern politics focuses heavily on how to make sure that humans have enough “stuff”. To be fair, a society cannot thrive if its citizens lack sustenance, shelter, and healthcare. Religious groups rightly devote enormous amounts of energy to serving the poor. The meeting of material needs is necessary, but it is not sufficient for a truly flourishing society, because it does not address the existential poverty that can afflict even the wealthiest person. As psychologist Viktor Frankl lays out in Man’s Search for Meaning, it is possible to have all one’s material needs met, yet still experience despair. He speaks compassionately of his patients who are “haunted by the experience of their inner emptiness” due to a “feeling of the total and ultimate meaninglessness of their lives” (128). He prescribes not more physical comforts, but rather more tension, as a tonic to this malaise: “What man actually needs is not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for a worthwhile goal…What he needs is not the discharge of tension at any cost but the call of a potential meaning waiting to be fulfilled by him” (127). His psychological theory echoes Christ’s response to the Devil in the Gospel of Matthew. When Satan tempts the fasting Christ to turn stones into bread, Jesus responds by emphasizing the spiritual needs which only God can fulfill: “But he answered, ‘It is written, “Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.’”

Furthermore, the focus on only material needs betrays an underlying materialist philosophy. Materialism undercuts the very possibility of the Good, since Goodness is not a physical entity we can see and touch. The historian Yuval Noah Harari recently gave a startling example of this tension between materialism and the metaphysical Good. On the one hand, he voiced a materialist objection to the concept of human rights, saying, “Human rights, just like God and heaven, are just a story that we’ve invented. They are not an objective reality; they are not some biological effect about homo sapiens. Take a human being, cut him open, look inside, you will find the heart, the kidneys, neurons, hormones, DNA, but you won’t find any rights.” Yet Harari frequently speaks out on social justice issues, giving moral counsel on wars, the pandemic, climate change, and more. His clear belief in moral standards for human behaviour stands at odds with his materialist commitments. Materialists who want Goodness are forced to “borrow” from metaphysical philosophies, but they weaken their own implicit ethic that it is good for humans to have their material needs met; they saw off the proverbial branch on which they sit. In a materialist culture where “God is dead,” Christianity will have to contend with an increasingly “post-Goodness” world. Atheist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre famously wrote, “Everything is indeed permitted if God does not exist.” Without Goodness, there is only power. Unlimited freedom inevitably devolves into power struggles. In this context, Christianity will have a far more difficult time convincing people to protect the vulnerable. The desire for the Good cannot be eradicated from the human heart, but it can certainly be numbed, and long enough for plenty of social damage to happen.

A transcendental even more under attack than Goodness is Truth itself. One of its current adversaries is the ideology of postmodernism. When Jean-François Lyotard first formally conceptualized postmodernism, he defined it as “incredulity toward meta-narratives.” Since this famous declaration, the ideology has had many adherents, but it evades strict definitions. In the Stanford Encyclopedia entry on the topic, Gary Aylesworth writes, “That postmodernism is indefinable is a truism. However, it can be described as a set of critical, strategic and rhetorical practices employing concepts such as difference, repetition, the trace, the simulacrum, and hyperreality to destabilize other concepts such as presence, identity, historical progress, epistemic certainty, and the univocity of meaning.” Aylesworth also traces, in postmodernism, a rejection of objective reality in favour of “de-realization.”

Contrast this destabilizing force with the Christian ethos. Christianity argues for the objectivity of Truth, and argues that we must align our subjectivity with objective reality. Jesus Christ insists that He alone is “the Way, the Truth, and the Life”—a statement at loggerheads with the postmodern impulse for endless interpretations. If materialism doesn’t see enough, by rejecting the metaphysical, then postmodernism sees too much. It rejects the “confines” of reason, or of a specific meta-narrative, in favour of an infinite array of interpretations without a conclusion. In this view, Christianity is simply a tyrannical imposition of arbitrary rules.

Consider the outrage against Christianity in the heated “gender wars” of our times. Transgender ideology is very much the offspring of postmodernism, with its prioritization of radical subjectivity over objective reality. If someone’s self-perception clashes with biology, then biology itself is viewed as a tyrant to be deposed. This is Andrea Long Chu’s argument in his recent article, “Why Trans Kids Have the Right to Change Their Biological Sex”. Chu writes that “sex itself is becoming a site of freedom”, but later clarifies what he really means: that without the unhindered ability to change one’s sex, biological sex is a force of tyranny. “Biology could not justify the exploitation of human beings; indeed, it could not even justify biology, which was just as capable of perpetuating injustice as any society,” writes Chu. In other words, any hindrance to one’s self-perception–including biology–is oppressive. Chu therefore views Christianity as bigoted for refusing to uphold any-and-all personal constructions of sex. When describing “the anti-trans bloc in America”, he says, “The first, and most obvious, [group] is the religious right, a principally Christian movement that holds that trans people are an abomination1.” Christianity’s insistence on objective Truth is sadly portrayed as hateful tyranny by those who prefer an infinite array of possible interpretations. But the lack of a transcendent standard for Truth ultimately produces not freedom, but rather despair. After all, freedom itself is unintelligible in a Truth-less universe. Without the light of objective Truth, we stumble in a dark cosmos with no inherent meaning and no final destination.

Both materialists and postmodernists treat Goodness and Truth as relative at best, and tyrannical at worst. How can Christianity contribute to the common good in this hostile environment? One path forward is the “via pulchritudinis,” the “Way of Beauty” (and I am indebted to Bishop Robert Barron for introducing me to this concept).

Beauty pierces the soul. When we encounter true Beauty, we do not experience a mere subjective preference. Consider the word “awestruck”: we do not simply “choose” to manifest awe, but rather, it strikes us, as if from the outside. People can reject the Truth and sneer at the Good, but it is difficult to avoid the instinctive pull of the soul towards the Beautiful, and only the willfully resentful would describe Beauty as “tyrannical.” Where modern societies prioritize utility over aesthetics, Christianity should move precisely in the opposite direction. We need cathedrals that stun us into silence. We need gardens in our noisy cities, to inspire peace and contemplation. Those who are drawn to the Beauty of God Himself should let their praise overflow into beautiful creations that will strike awe into others. The piercing experience of Beauty cuts through the endless rhetoric of postmodernism, and points to spiritual realities beyond the material. As the great theologian G.K. Chesterton once wrote, “There is a road from the eye to the heart that does not go through the intellect.” By acting as an unapologetic arbiter for Beauty in the public square, Christianity can touch the human heart and awaken the dormant desire for the Transcendent—the hunger only God can satisfy.

- I categorically reject the view that someone experiencing gender dysphoria or discordance is an “abomination”. That person is made in God’s image and likeness, and deserving of compassionate help. If the confused mind rejects or loathes the body, we should help the person experience mental healing and self-acceptance, not affirm the distorted view that the body itself is flawed.

If gender dysphoria is part of your experience, I encourage you to check out the wonderful community at Eden Invitation. ↩︎

- I categorically reject the view that someone experiencing gender dysphoria or discordance is an “abomination”. That person is made in God’s image and likeness, and deserving of compassionate help. If the confused mind rejects or loathes the body, we should help the person experience mental healing and self-acceptance, not affirm the distorted view that the body itself is flawed.

-

Guest Appearance on “The Pro-Life Guys Podcast”

I was very thankful for the invite to be a guest on The Pro-Life Guys Podcast, as part of their “Humans of the Pro-Life Movement” series. It was a great discussion with Cam Côté, a friend and colleague in the movement. Check it out:

-

No Man is an Island (or, the myth of autonomy)

We enter this world helpless, vulnerable, and dependent. Most of us will also end life in a state of vulnerability and dependence. And between the beginning and the end, we will all experience periods, long or short, when we’ll desperately need the help of others.

Some of us go from a healthy high school athlete to suddenly living with the immense challenges of long-Covid. Some of us will need a wheelchair for a few days after hip surgery, and some of us will need to use a wheelchair for the rest of our life after a car crash. Some of us find our fierce independence sharply interrupted by a depression so deep that we can’t buy our own groceries or clean our own house. We rely on our loved ones to buoy us through the stormy seas.

I remember, as a young girl, peering through the hospital glass at my premature baby brother. He was attached to countless wires and tubes, and was fighting for his life. Miraculously, he survived. God’s grace worked through the caring hands of countless doctors and nurses, to save this unbelievably tiny person.

As a teenager, my summers were usually spent swimming and playing soccer. But at age 16, I spent most of my summer beside my dying Dad. After his diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, we thought we’d have 6 months with him. Instead, we had 6 weeks. My powerhouse of a father, who literally helped write the book on getting things done, became weaker and weaker. But love’s strength doesn’t rely on physical strength, and he poured out his love to us and to all his community. In his last moments, all we could do was hold his hand and silently bestow our love on him.

Interdependence is a fundamental aspect of the human condition. A loss of autonomy–whether temporary or permanent–does not mean a loss of dignity, and it is grossly ableist to suggest the opposite. When we demonize dependency, we demonize our very humanity.

Let us bless the vulnerability and poverty in the face of the Other. We can start by looking in the mirror.

-

You’re not a mistake.

The apples we place in our grocery carts are all perfectly round. Each red rose in the bouquet from our local florist is the same size and the same shade as her companions. When we don’t spend much time in uncultivated nature, we sometimes end up thinking that plants always look so similar to each other.

But then, Nature stuns us with her variety. Crooked purple carrots push up through the soil, knobbly yellow apples fall from the trees, and asymmetrical roses blossom.

This one probably won’t end up at your florist’s shop. But are her differences a flaw–or part of her unique beauty?

If you’re anything like me, maybe you’ve caught yourself in this kind of thinking pattern: “I wish I had her looks. I wish I had as many degrees as him. I wish I had their kind of marriage. I wish…”“God, why did You make me like this? God, why did You put me on this path, and not that one?”

It is OK–more than OK– to grieve if your life doesn’t look the way you wished it did. Let’s also remember, though, that we’re the children of an infinitely creative God, and His glory manifests itself in an infinite number of ways. Is it possible that your unique self and unique plan is a blessing to be embraced, not a flaw to be fixed?

We all have to grow in sanctity. But sanctification means God pruning us and nourishing our soil–not replacing us with a “different plant”.

God didn’t have to create you. So if you exist, in all your unique glory, it’s because He wants you to be here.This short reflection was written for my friend Magda’s blog/ministry, Girlfriend Restored. Check out her reflections and resources for those affected by betrayal trauma at girlfriendrestored.com

-

Poetry Rx

Dear patient,

Your prognosis is unclear. The treatment journey for your chronic illness will be complex. As a start, please add in iron supplements, to improve your energy levels. I am also prescribing some poetry, to fortify your spirit.

These “prescriptions” are actually, in the main, descriptions. They are not curative; rather, they will anchor and organize your thoughts. But you will discover the value of a vivid word-anchor, on the days when your mind is tempest-tossed by appointments and needles and waitlists and specialists and the unsolicited medical advice of strangers.

For When You Want to Shout at God for Answers

‘My nerves are bad tonight. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.

What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

I never know what you are thinking. Think.’

– The Waste Land, TS Eliot

For When Shouting at God Feels Pointless

Ay me, to whom shall I my case complaine,

That may compassion my impatient griefe!

…To heavens? Ah! they, alas! the authors were,

And workers of my unremedied woe:

For they foresee what to us happens here,

And they foresaw, yet suffred this be so.

– The Dolefull Lay of Clorinda, Mary Sidney Herbert

For When You Just Want Your Old Life Back

“But those two circles, above all the point at which they touched, are the very thing I am mourning for, homesick for, famished for. You tell me ‘she goes on.’ But my heart and body are crying out, come back, come back. Be a circle, touching my circle on the plane of Nature. But I know this is impossible. I know that the thing I want is exactly the thing I can never get.”

– A Grief Observed, CS Lewis

For When You Grieve the Healthy Future You Thought You’d Have

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose-garden. My words echo

Thus, in your mind.

But to what purpose

Disturbing the dust on a bowl of rose-leaves

I do not know.

– Four Quartets, TS Eliot

For When You Know, Bone-Deep, the Etymology of “Patient”

I have given my name and my day-clothes up to the nurses

And my history to the anesthetist and my body to surgeons.

…My body is a pebble to them, they tend it as water

Tends to the pebbles it must run over, smoothing them gently.

They bring me numbness in their bright needles, they bring me sleep.

– Tulips, Sylvia Plath

For When You Feel Useless to the King and Kingdom

“Doth God exact day-labour, light denied?”

I fondly ask. But patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies, “God doth not need

Either man’s work or his own gifts; who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state

Is Kingly. Thousands at his bidding speed

And post o’er Land and Ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

– Sonnet 19: When I consider how my light is spent, John Milton

For the Waves of Pain Before the Anesthesia Kicks In

For When You Need the Motherly Mystics

Let nothing disturb you,

Let nothing frighten you,

All things are passing away:

God never changes.

Patience obtains all things

Whoever has God lacks nothing;

God alone suffices.

– St. Teresa of Avila

For Every Moment of This Journey

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.– Go to the Limits of Your Longing, Rainer Maria Rilke

-

What is the duty of the living?

Retired Cpl. Christine Gauthier had been trying for 5 years to get Veterans Affairs Canada to install a wheelchair ramp at her house. The former Paralympian was speaking yet again with the VAC, describing the disability-related challenges she was facing. Eventually, an employee suggested that if life was becoming so difficult for her, perhaps she would prefer receiving physician-assisted suicide? They could even supply her with the MAID “equipment”.

Gauthier said of the encounter, “I was completely shocked and in despair.”

Another Canadian veteran reached out to Veterans Affairs, looking for mental health support. The caseworker instead repeatedly offered the man assisted suicide, despite the fact that the veteran had never asked for it. He reported that his VAC caseworker said to him, “Oh by the way, if you have suicidal thoughts, [MAID is] better than blowing your brains out against the wall.”

A much cleaner solution. Maybe that’s why they use the euphemism “MAID.”

Although the gentleman had been in a good place prior to the call, he was so shocked afterwards that he left the country. It’s a phenomenon known as “sanctuary trauma,” where a person is left immeasurably harmed by the very people he thought would help him.

Speaking of sanctuary, have you heard of the latest bold solution to the problem of homelessness? Apparently, nearly a third of Canadians from a variety of demographics support MAID for those who are homeless. The message is loud and clear: if you can’t afford a house, we can give you a body bag.

How quickly the so-called “right to die” becomes a duty to die. And how easy it is for a vulnerable person to believe the lie that she should erase herself if her needs take up “too much space” in the community.

The slope is indeed slippery, friends. And another word for a slope that’s approaching ninety degrees is cliff.

It would be easy to turn a blind eye to the medicalized executions happening in our midst. But I propose to you that instead, we be our brother’s keeper, and his lifeline. We cannot abandon him in his moments of crisis and confusion. We have to help him remember his reasons to stay when dark voices whisper the reasons he ought to go.

And the best way to honor those already lost is to make sure that no more victims are added to the body-count. As Lois McMaster Bujold has written, “The dead cannot cry out for justice. It is a duty of the living to do so for them.”

If you are struggling with suicidal ideation, please know that you are not alone. You can find crisis support resources here. You are irreplaceable, and deeply loved. You deserve to be here.

To take action against the expansion of euthanasia in Canada, visit Care Not Kill.

-

Valued and Loved

CW: Brief description of intimate partner violence

“I don’t want to play God and decide who lives and who dies,” Helen said reluctantly. Nevertheless, she still thought that abortion was needed in many difficult circumstances. If a woman felt unready, or was battling poverty, how could she care for the child? She spoke at length of her concern for women and girls in bad situations, and I did my best to listen intently. “I agree with you that getting pregnant when you’re in a bad situation would be really scary,” I said to her. “A woman facing that definitely needs our help. Imagine with me, though, that there’s a woman who during pregnancy is in a good situation. Her finances are stable, and her partner is supportive. But after she gives birth, things change–she suddenly loses her job, and her partner walks out on her.”

I paused, then asked: “Would it be OK for her to kill her newborn baby, because she’s facing so many difficulties?” “Of course not,” Helen answered. “I agree,” I said. “So, if it wouldn’t be OK to kill a born child because the mom is facing so many difficulties, why would it be OK to kill a pre-born child for the same reason?” Behind me, on our signs, were photos of the broken bodies of aborted children.

Helen thought about this, and then gave voice to the painful memories that fuelled her support for abortion. “My mother was horribly abused and beaten while she was pregnant with me,” she told me. “And she was very poor. She should have just gotten an abortion. Things would have gone better, and been easier for her.”

In a few short sentences, she conveyed layers of trauma. Her mother was a survivor of assault, and so was she. The abuser had treated both women like worthless trash.

Many people can have a hard time valuing pre-born children if they don’t first know their own value. I wanted Helen to know the truth: that she and her mom were precious and worthy of care.

“I’m so sorry your mom went through that,” I said to her. “That should have never happened to her. If you don’t mind me asking, is she safe? Is the abuser still in her life?” Thankfully, her mom had escaped the situation, but had then endured great poverty. Helen truly believed that it would have been better if her mother had aborted her.

“Do you think your mom feels the same way?” I asked gently. “Do you think she wishes she’d had an abortion?” I was prepared for the response to be Yes, because I have met people whose parents have said just that. I was glad that Yes was not the answer given. “No, she would never say that,” Helen immediately replied. “She would say that she would go back and choose me all over again.” I asked some more questions about Helen’s story, and she told me that she was now caring for her aging mom.

“Leaving aside abortion for a moment”, I said, “I just want to emphasize that it really sounds like your mom’s life is actually better for having you in it. She loves you, and you love her, and she knows that you love her. And you’re helping to care for her now. There are so many people who wish they had that kind of love in their life. So I just want to emphasize that her life is better with you in it, and I don’t think we should assume that her life would have been better without you.”

Something shifted in the tone of our conversation, at that point; she seemed moved, and became more open to the pro-life perspective.

Our value as humans is not contingent on whether other people love us, but it can be incredibly hard to know our own worth until we have experienced the love of other people–and ultimately, the love of God.

Man cannot live without love. He remains a being that is incomprehensible for himself, his life is senseless, if love is not revealed to him, if he does not encounter love, if he does not experience it and make it his own, if he does not participate intimately in it.

Pope St. John Paul II, REDEMPTOR HOMINISHelen and I went on to discuss many other aspects of the abortion debate, such as whether pre-born children were equally valuable to born children. We talked about the legal and cultural shifts needed to protect the pre-born and support women and girls. Helen spoke with conviction about how important it is for a man to step up and support his partner during pregnancy, rather than pressuring her to have an abortion just so he can evade the responsibility of fatherhood.

As outreach was ending, I asked Helen, “Thinking about abortion in light of what we’ve discussed, do you think there’s any situation where it’s OK?” She thought about this question, then told me that she was still unsure about cases where the woman’s life was in danger or the baby had a terminal illness. I encouraged her to keep thinking about the issue, since abortion profoundly affected so many people. We shook hands and I thanked her for stopping to speak with me.

-

Taxi Rides, Disability, and Unexpected Grace

I had an unexpected and beautiful encounter with my cab driver today in Toronto. He called me because he was having difficulty stopping at my location, and he asked if I could walk to another place nearby. I nervously replied that I couldn’t because of my disability. (My hips and back were aching, making walking difficult.) Rather than being annoyed, he was instantly understanding and said he would come right to my spot.

It was, indeed, not a great stop because it was so close to a ramp to the Don Valley Parkway. As he pulled over, a large truck behind him honked angrily. He got out of his car to help me with my luggage, and shouted at the truck drivers, “She has a disability!” (Had I been a turtle in that moment, my head would have retracted into my shell.) He motioned for them to roll down their window, and told them that he had to stop there in order to accommodate me.

I felt nervous and sheepish. Was his shouting at them a sign that he was annoyed with me? I got into the cab, offered my apologies for the trouble, and settled in for the drive.

After a couple of minutes, he said to me, “Can I ask you a question?” I braced myself to be asked why I didn’t have some sort of mobility device with me to signal that I was disabled. Instead, he opened up and told me that his younger brother in his native country had a cognitive disability and needed a lot of care. He was working as hard as he could to bring his brother over to Canada. “I want to have him with me for the rest of my life,” he said, with conviction in his voice.

He asked me what sort of supports, if any, were available in Ontario for people with disabilities. I told him that although the system was far from perfect, there were many supports. I explained a bit about ODSP and the medical process to get it, some social services for people with different challenges, and so on. I added in that the process to attain those supports would take longer for someone immigrating to Canada, and we talked about the steps he himself had taken to come here. I was taken aback when he said that he was so thankful to have me as a rider, because he didn’t know anyone to talk to about his situation, and he desperately wanted to provide the best care for his brother. He found it more helpful, he said, to speak with people who had personal experience navigating the system, rather than only talking with people in bureaucracy. He said that I had given him more hope for the future, because now he knew that there were resources available to help his brother.

I asked him a bit about his brother, and he explained the challenges that the young man faced. He said that everyone needs a reason to live for, and a major reason for him was his relationship with his brother. He first emphasized the importance of duty to one’s family. Then, he went on to talk about how, when we sacrifice out of love for others, our lives paradoxically becomes enriched rather than diminished. I was so encouraged by his love for his brother, and told him a bit about my own younger brother and his complex medical needs. (My brother has faced massive challenges throughout his entire life, and yet has the most joyful spirit of anyone I know.) The driver and I talked about how everyone benefits when we work to build a more inclusive society for people of all abilities.

Our culture frequently criticizes toxic expressions of masculinity, and those expressions certainly exist. I think we also need to remember, though, that if toxic masculinity is so ugly and repulsive, that simply shows that authentic masculinity is supposed to be beautiful and inspiring. I saw that expression of true masculinity in my driver today. He was willing to firmly stand up for my need for accessibility, even though it irritated people around him. He was committed to loving the most vulnerable people in his life, and he perceived the mystery that it is in giving that we receive.

-

“Shouldn’t we talk more about adoption?”

I recently gave a pro-life presentation on how to have effective conversations about abortion. The talk focused on discussing science and human rights with pro-choice people, to help them understand that abortion is a human rights violation against an innocent child.

During the Q&A session, a participant asked me a question that I’ve heard often from pro-lifers: “Shouldn’t we be talking more about adoption? There are long waiting lists of couples wanting to adopt children.” I could see where he was coming from. After all, if a woman is pregnant but does not feel prepared to care for a new child, isn’t adoption a solution to her situation, and a way to bless another couple with the gift of a child? Shouldn’t we then recommend that, in our conversations with abortion supporters?

“That’s a great question,” I said to him. “There are definitely times and situations when it is appropriate to discuss adoption in our conversations about abortion. However, I almost never bring it up early in the conversation with a pro-choice person–for two reasons.”

“First of all,” I said, “By jumping to promoting adoption, we accidentally end up sidestepping the question of whether abortion is moral or not. For instance, imagine that World War III broke out tomorrow and adoption was suddenly impossible in Canada. Would abortion suddenly become OK, just because there are no adoptive parents available? I would say absolutely not, because abortion still kills an innocent child.”

And my analogy is not far-fetched; that kind of situation could easily happen to people who are fleeing a violent country, for instance. What if they spend months in a refugee camp, and cannot find anyone to adopt their 2-year-old child? Would it be okay for them to kill their toddler due to the lack of adoptive parents? Most sane people would answer, Of course not. But if it wouldn’t be okay to kill a born child, even if there are no adoptive parents for him, then why would it be okay to kill a pre-born baby for the very same reason? But that’s different, the pro-choice person may answer. It’s not a human yet. We must then return to the central question of the abortion debate: who are the pre-born? Are they living human beings, deserving of equal rights?

I continued, “The second reason that I avoid discussing adoption, at least early in the conversation, is because of a common negative perception of adoption by many pro-choice people. Many pro-choice people actually view adoption as worse than either abortion or parenting.”

The thought process of the pro-choicer goes something like this: while abortion is undoubtedly difficult for a woman to go through, it at least “solves” the problem of her unwanted pregnancy by ending the pregnancy. She can avoid having her life irrevocably altered by an infant. If she chooses to carry to term and parent, then she does deal with the difficulties of pregnancy and an altered life trajectory, but she will hopefully experience love and connection with her newborn baby.

When many pro-choice people consider adoption, they view it as the worst option, because not only does the woman go through the difficulties of pregnancy, but she also will bond emotionally to the baby. Adoption will then inflict a wound of separation on her and her baby. I’ve heard many pro-choice people say that the woman could spend her whole life wondering how her child is doing, and the child could spend his whole life feeling abandoned or unwanted. (Some people also mistakenly conflate the newborn adoption system with the foster care system, and worry that the child could go for years without a permanent adoptive family.)

There are some untruths mixed in with all three of these views. I have met countless women and men who discovered that abortion was not an easy and painless choice, but instead led to deep grief and regret. It did not prevent them from becoming parents–it simply made them the parents of a dead child. Improved adoption systems can help biological parents to connect or re-connect with their children, when it is possible and appropriate to do so. And I have dear friends who are adopted, who lead lives filled with love and purpose. The late Steve Jobs was adopted, and spoke of his gratitude for his birth mom’s courage: “I wanted to meet my biological mother mostly to see if she was okay and to thank her, because I’m glad I didn’t end up as an abortion. She was 23 and went through a lot to have me.”

However, even if the pro-choice assumptions are all correct–even if abortion involves the least emotional pain for the mother, and adoption involves the most pain–this still would not justify the violence of abortion, any more than it would justify killing a one-year-old child.

So, I said to this gentleman that I thought it would be more effective to first talk with a pro-choice person about why abortion is an injustice, and should not even be an option on the table. Once we’ve reached a consensus on that, then we can have compassionate discussions about how to best care for the child, and whether adoption is an appropriate route to pursue. My lovely friend Gabrielle, an adopted person herself, put it succinctly:

“The moral issue of abortion is cut and dried, but the social issue of unplanned pregnancy is not.”

On that note, pro-life people also should acknowledge that placing a child for adoption will involve pain for all parties involved–the biological parents, the adoptive parents, and the child. If we simply respond, “But she can just put the baby up for adoption!”, the pro-choice person will likely think that we are (at best) naïve to the traumas that can accompany the adoption process. We don’t want to give the false impression that adoption is “magical fairy dust” that we can sprinkle on an unplanned pregnancy, to “fix” the situation for everyone involved. Gabrielle has spoken openly to me about her experiences with adoption, both the blessings and the hardships. She emphasized to me that while she is deeply grateful for her life and her family, she also faces challenging questions about her identity, her origin story, and her family relationships. We can defend the human rights of pre-born children, without ignoring the complexities of adoption.

A final word of caution, when we are speaking about adoption: some people talk about adoption as important because it can allow infertile couples to raise children. This well-intentioned statement unfortunately glosses over the painful realities of infertility, which cannot simply be “fixed” by adopting a baby. Gabrielle told me that this viewpoint also pains her, because it treats adopted children as commodities, as “solutions” to a problem, rather than as people deserving of love. Adoption should always prioritize fulfilling a child’s need for (and right to) a loving family, not fulfilling the desires of adults for children.

What do you think? How have discussions about adoption played into your conversations about abortion?

This article was also published in Dutch for the organization Kies Leven: https://kiesleven.nl/zouden-we-het-niet-vaker-over-adoptie-moeten-hebben/