-

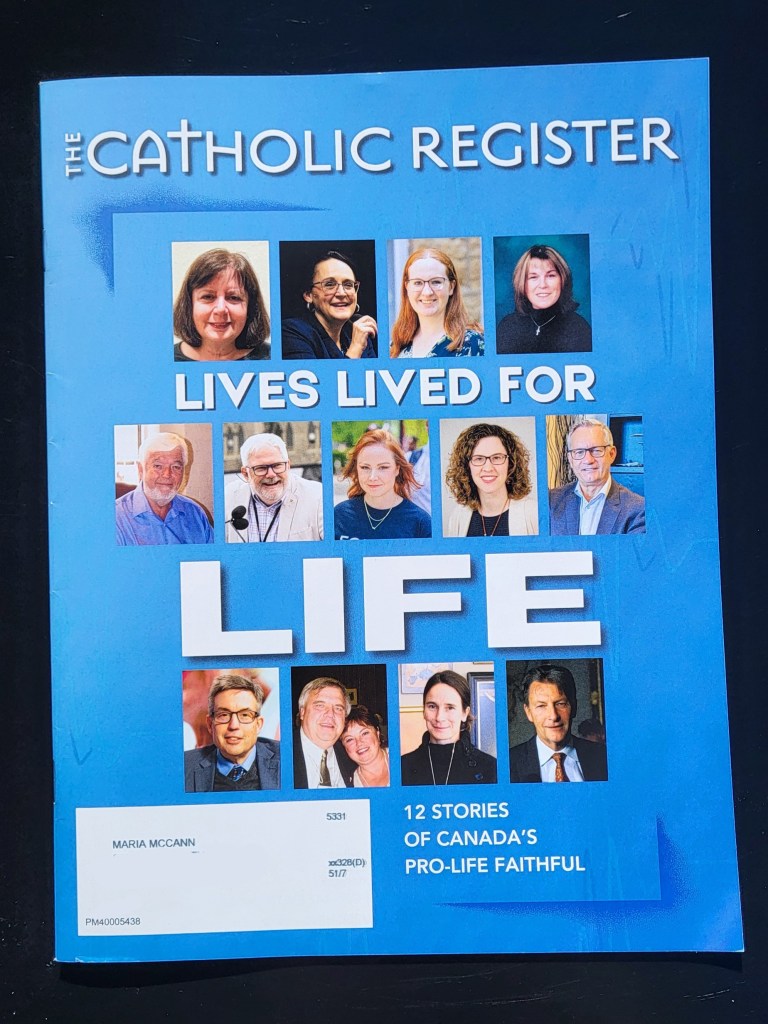

“Lives Lived For Life” Magazine

Earlier this year, I was interviewed by the Catholic Register about my involvement in the pro-life movement. I was overwhelmed and humbled to be included in their “Lives Lived For Life” issue, a special edition which highlighted 12 stories of pro-life Canadians.

My prayer is that anyone who reads the issue realizes that every one of us has a role to play in ending abortion. The pro-life movement is not about me or about you. It’s about our pre-born neighbours, little girls and boys, whom God calls us to protect from slaughter.

Get Involved: EndTheKilling.ca/TakeAction

I’m so grateful for the support of my family in doing this work, and for the countless pro-life colleagues who’ve become a second family.

Soli Deo honor et gloria!

-

Lobbying for Paratransit Reform

Yesterday, I had the opportunity to speak briefly at a London City Council meeting. I talked about the challenges I have faced while using the London paratransit system, and shared some ideas for improvement. Paratransit has been in the local news frequently (e.g. here, here, and here) for posing problems to its users, and the disability community in London has been very vocal on the issue.

Check it out:

-

Welcome to my blog!

Hello, and welcome to my blog!

My name is Maria, and I live in Ontario, Canada. I am a Catholic woman, a daughter, a sister, a #CoolAunt, and a friend. I am also a pro-life public speaker–you can read more about that here.

In this space, I hope to share my reflections on social issues, such as the abortion debate, disability rights advocacy, and other matters of human dignity and flourishing.

I have lived with chronic pain for about 7 years. Developing chronic pain in your early twenties is not the future anyone prepares for, and the challenges of my disability have sometimes been extreme. I am fortunate to have a web of family and friends who have supported me in the most intense trials. I hope that by writing about my experience with chronic pain and with the medical system, I can process some of those experiences for myself, and help other people in similar situations to feel less isolated and more empowered.

Besides social advocacy, I am also deeply passionate about literature, philosophy, and theology. I am always looking for ways to dive deeper into these subjects and grapple with their complexities. I want to pursue the Good, the True, and the Beautiful.

If you want to read more and join the conversation, subscribe to receive future blog posts!

-

The Truth is a Light in the Darkness

Originally posted on November 16th, 2020 for the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform

“A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.”These lines from T.S. Eliot’s 1922 poem The Waste Land have long haunted me, especially in the context of the abortion debate.

Could Eliot somehow see into the future and visualize what a “Choice” Chain looks like? Of course not, my rational side thinks; he was simply speaking about the terrible social isolation he was witnessing in his own time. Suffering and loneliness and the impact of death are by no means new phenomena. Nevertheless, I have been reminded of his words many times when I have gone out to do activism.

The parallels are almost eerie. As we stand on street corners for “Choice” Chain, crowds of people will mill past, their eyes usually cast downward towards their cellphones. And when they do look up — often startled, understandably, by the unusual question “What do you think about abortion?” — their apathy often suddenly transforms into anger, which often masks underlying grief. I have lost count of the number of post-abortive people that I have met in the 5 years that I have been involved with CCBR. Millions of tiny corpses do not simply disappear in a vapour cloud of ‘choice’; a scarred society is left behind. Death has undone so many.

And yet, there is so much reason for hope. I have heard it said that it is better to light a candle than to curse the darkness. I agree with the sentiment, but the wonderful thing is that the truth isn’t just a faint candle. The truth is a roaring fire, dispelling both the shadow of death and the chill of empty ideologies.

I remember speaking, for instance, with a young woman named Olga, several summers ago in Toronto. She stopped because she was curious about our signs and our views, but she supported abortion and said that she was not sure what she herself would do in an unplanned pregnancy situation. She especially thought that abortion was needed to prevent future suffering for the child. I spoke with her at length, but nothing seemed to get through and she remained obstinately pro-choice.

Unsure how to continue the conversation, I tentatively shared with her what I had learned from philosopher Viktor Frankl about suffering. I told her that suffering did not have to lead to despair, because although we will all suffer at some point, it is possible to find meaning in even the darkest situations. That was the proverbial “light bulb” moment for Olga. She responded with passionate agreement, and we talked about how we would both try to help people find meaning in the face of immense suffering. We talked about the importance of preventing lethal choices like suicide as a response to suffering. Olga then made the connection that abortion, like suicide, was a tragedy rather than a solution. Before leaving, she said to me, “You’ve definitely pushed me towards the pro-life end of the scale. I’ll never get an abortion. There’s always another way.” When she considered a philosophy built on hope rather than despair, her heart changed and softened towards the pre-born baby.

Eliot’s poem The Waste Land is a long, grim survey of a 1920s world reeling from recent war. As the title suggests, the very earth itself seems to cry out in anguish. Nevertheless, the speaker in the poem takes a hopeful turn towards the end, when he notes that rain is coming to revive the arid landscape. Faint hope further lies in the speaker’s concluding thoughts: These fragments I have shored against my ruins. Stories, flickers of light here and there, are enough to at least provide him with hope. And I think of the testimonies like that sometimes. The darkness of abortion can be overwhelming—death has undone so many—but my mind is also filled with story after story of people whom I have seen, before my own eyes, go from supporting abortion to rejecting it. The testimonies are fragments of hope and healing to shore against a crumbling culture.

However, I have even firmer reasons for hope. A plethora of anecdotes is not data. Stories by themselves are not enough. We need firm evidence that our work is changing the culture, and saving children. But we have the data – the hard numbers that show that simply seeing abortion victim photography changes people’s perceptions of abortion. The testimonies are then merely reflections of those stats; stories are ‘data with a soul’, as researcher Brené Brown puts it.

And I have a firmer reason still for hope in the face of abortion and all the shadows of this world. It’s a hope that eluded Eliot at the time of his writing The Waste Land, but one that he eventually embraced in his conversion to Christianity later in life. We grieve at the deaths of countless children, but we do not grieve like those who have no hope. Death does not have the final say. When the light shines in the darkness, the darkness does not overcome it.

-

Speaking with Survivors

Originally posted on April 27th, 2020 for the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform

It is a question that you will be asked in nearly every conversation about abortion. What about when a pregnancy has resulted from a heinous act of violence? What about pregnancy in the case of sexual assault? Abortion supporters often ask this question in a hypothetical sense, and we should be able to provide a compassionate and logical answer about why we need to protect both the mother and the baby. Some people, however, are not thinking of a hypothetical situation, but instead of an all-too-real memory.

I remember speaking with Alex* some time ago during a college “Choice” Chain. She disclosed her experience at the very beginning of our conversation: “I get that you guys are pro-life and stuff, but what about rape? I was raped when I was a teenager. Do you think that even in situations like mine, women still shouldn’t have abortions?”

When someone discloses a traumatic experience, there is no blueprint for the “perfect” response. I think that we can, however, take guidance from authors Mary Schaller & John Crilly. In their book The 9 Arts of Spiritual Conversations, they write, “Asking questions from genuine interest builds connection. Connection builds trust. Trust is the bridge that can bear the weight of truth.”

The first thing that I said to Alex was, “I’m so sorry that that happened to you. I want to answer your question but first, I just have a question for you. Are you safe? Is the person who hurt you still in your life?” Alex told me that the assault had happened a few years ago, and the perpetrator was thankfully no longer in her life. (If the assault had been more recent, it may have also been appropriate to ask her if she had reported the assault, or wanted to.) I asked her if she had people in her life who were supporting her in her healing journey, and she mentioned that there were people such as her mom who were helping her.

I continued asking questions as gently as I could, and I focused on really listening to Alex. She shared her story of being sexually abused in high school, and the eating disorder she had developed as a result of trying to cope with her trauma. I affirmed her value and emphasized that what had happened to her was not okay.

At one point she said to me, “What about women who are walking by who may have had abortions? How do you think these photos would make them feel?” I replied to her, “I agree with you that there may be women walking by right now who have had abortions, and seeing these photos would be really difficult for them. But the reason we are here is not to condemn people for the choices they’ve made in the past. We are here to offer information to help people make better choices in the future.” I pointed down at my sign at one point and said to her, “I refuse to believe that this is the best we can do for women and their children.”

We continued talking and a little while later she said to me, “I know that you’re not here to judge women who’ve had abortions.” She then disclosed to me that she had become pregnant as a result of the assault, and had had an abortion.

Again, I asked her gentle questions about her abortion and what she thought about it now. I told her how sorry I was for everything she had gone through. We found common ground by agreeing that society needed to do more to support women and their children.

Alex told me that she didn’t like to think about the abortion much because it was in the past, and she didn’t want to have regrets about the past. I then shared the Choice42 website with her and told her about the groups that exist for people who seek healing after abortion. “Maybe this resource won’t be useful to you today or tomorrow,” I said to her, “but maybe you could find that useful sometime in the future.”

Alex agreed with me and accepted the resource card, and she asked me more questions about why we were against abortion. And I didn’t shy away from those questions. I continued to share the truth with her about the humanity of the pre-born and the inhumanity of abortion. Because as my friend Devorah has often said, truth without love is ineffective — but love without truth is a lie. We need to share both.

By the end of our long conversation, Alex still identified as pro-choice. However, she had seen the truth, had heard the truth, and had heard that there was the possibility of healing and forgiveness after abortion. And I was so grateful when she said to me, “You’re starting to sway me. You’ve definitely opened my mind. When should a human being get human rights? That’s not something I’d ever thought about before.”

*Name changed to protect privacy

-

What About a Woman’s Right to Choose?

Originally posted on November 1st, 2018 for the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform

While at a pro-life display with Toronto Against Abortion, I asked a young woman what she thought about abortion. The student, Sharon, told me that she was pro-choice. “Is there any particular reason that you’re pro-choice?” I asked, for clarification. Sharon said, “I think that it’s important for women to have a choice about having a child. Especially if they weren’t planning on getting pregnant.” She told me that she was not sure what she herself would do in an unexpected pregnancy.

Many people will bring up difficult circumstances, such as suffering or cultural pressure, to justify abortion; however, it is even more common for people to bring up the right to choice and bodily autonomy as the justifying factors. Abortion supporters typically brand themselves not as “pro-abortion” but as “pro-choice.” As pro-life advocates, we need to show people that our right to bodily autonomy does not include the right to harm or kill others.

“I would agree with you that the right to choices is important–especially choices about our own bodies,” I said to Sharon. “I think, for instance, that you and I should have the right to go to a bar and drink, even if drinking isn’t very healthy.” She nodded in agreement. “Imagine though,” I continued, “that after having a few drinks, I then get behind the wheel of my car. Would you still support my choice?”

“No, of course not,” she answered. “Why not?” I asked. “Well, because then you could harm other people.” “Yes,” I answered, “you wouldn’t support that choice–not because you don’t respect me, but precisely because you value other people’s safety.” I then pointed to the bloody 10-week aborted child in my pamphlet, and asked her, “So what about this choice? Doesn’t abortion harm another human being?”

Sharon thought about this question and looked at the photo. She then told me that later in pregnancy, the fetus seemed really developed and human, but abortion should still be acceptable earlier in pregnancy. “Earlier on, aren’t they not very developed?” she asked me.

We then discussed embryonic development as we looked at photos of first-trimester children — some healthy and alive, some dismembered by abortion. I shared with her some embryology facts, such as the child’s brain waves being detectable just after 6 weeks, and her heartbeat beginning at just 3 weeks. We continued talking about level of development and whether it should impact our human rights. She eventually agreed that human rights should begin as soon as a human being’s life begins–at fertilization.

To close the conversation, I asked Sharon if she still thought that abortion should be acceptable at any point in pregnancy. She replied, “When I came over here I was thinking about how important it is for a woman to have the choice. But I believe even more strongly that the baby shouldn’t be punished–nothing should be done to the baby.” I then emphasized to her the importance of supporting women during challenging pregnancies, as so many women entered abortion clinics precisely because they felt like they had no other choice. Sharon shook my hand, and although she had been pro-choice just 15 minutes earlier, she left our conversation completely pro-life.

-

When Does Life Begin?

Originally posted on November 27th, 2018 for the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform

As I was reading Maaike Rosendal’s new article about in vitro fertilization (IVF), it reminded me of a recent conversation I had with a student during “Choice” Chain. IVF has many troubling ethical implications, and I encourage you to read the article in order to understand how it harms and even kills many pre-born children. Discussing IVF can, however, help pro-lifers to show skeptical people an important truth: we know when human life begins.

I asked a student at York University what he thought about abortion, and offered him a pamphlet. Abdul stopped and started looking at the pamphlet, and told me that he didn’t have a strong opinion on abortion. He listed a couple of arguments from pro-choice and pro-life perspectives, and said that he wasn’t sure which side to believe. We discussed human rights, and he agreed that human rights should be for every human being. As we looked at the 7-week embryo on the pamphlet, he was surprised by how developed she was: “That sure looks like a human. Yeah, that looks like a person.”

I drew Abdul’s attention to the other photos of children aborted in the first-trimester, and I asked him what he thought about those photos. He told me that he now agreed that abortion from 7 or 8 weeks onward was wrong, because the child looked so developed. “I’m glad that we can agree that a huge percentage of abortions aren’t okay,” I said to him. “Why do you think that abortions are okay earlier than 7 weeks, though? Shouldn’t human rights begin when a human being’s life begins?” Abdul told me that he didn’t think that there is a full human being right at fertilization, because the zygote is a single cell and is so much less developed than 7 or 8 week embryos.

I said to him, “Let’s set aside for a moment the question of abortion and whether it ends a life. Let’s look at when we want to create a new human life. If I wanted to create a new human life, outside of the normal means of people having sex, what process would I replicate in a lab? Would I do in-vitro…heartbeat? Or in-vitro brainwaves?”

“No,” he said, “You’d do in-vitro fertilization.”

“And why is that?” I asked.

He answered, “Because that’s when everything begins…Oh wait, I see what you mean!”

It was just the ‘lightbulb’ moment that I hoped he would have.

We were going to continue the conversation, but Abdul realized that he was late for his class. We shook hands and he rushed off, pamphlet in hand. While I was not able to confirm whether he left completely pro-life, I know that he left with a new understanding of the humanity of even the tiniest embryo.

-

Are Human Rights for all Humans?

Originally posted on October 15th, 2018 for the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform

Alex had stopped, curious at our images and at my question— “What do you think about abortion?”—as he was heading to class.

“I’m pro-choice,” he answered.

“Pro-choice for what?” I asked.

“Uh, just pro-choice. I’m not sure what you mean.”

“Sorry,” I replied, “I don’t mean to be confusing. I’ve talked to a few people today who said they were pro-choice, but they all had different definitions of it. What does being pro-choice mean to you?”

We chatted for a couple minutes and he gave me some reasons why he supported abortion. I then asked him, “Do you believe in human rights?”

“Yes,” he replied.

“Great, me too! And who should get human rights?” I continued.

He became thoughtful—which is a great thing. We want people to consider their views more carefully! “Hmm…I think that humans who are rational and self-aware should get human rights.”

Though he did not explicitly use the word “personhood”, I realized that Alex was basically making a distinction between “persons” and human beings. I have heard people cite countless different standards which they believe a human being must meet in order to attain personhood. But these philosophical claims need not intimidate us. We can ask simple questions to help people understand that this distinction flies in the face of human equality. And “ask questions” is exactly what I did.

“I’d agree that our rationality is one of the things that makes humans special,” I replied. “I’m not sure though that it’s the reason we get human rights. Think of it this way: imagine there’s a man who’s in a temporary coma—for, say, 9 months. The doctor tells you that for those 9 months the man will be totally unconscious, but he’ll regain consciousness afterwards. Would it be OK to kill him during those 9 months, since he’s not self-aware?”

He considered this and said, “No, that’s a good point. I guess it’s more about whether or not a person is going to be happy and functional.”

I offered another analogy and question to challenge this: “Well, imagine that tomorrow, the unthinkable happens: you get into a car crash with some family members. Some of them die, and you become a paraplegic. You wouldn’t be very happy, and you wouldn’t be as functional, right? But wouldn’t you still get human rights?”

He considered the scenario and again replied, “Yeah, I don’t like that definition either.” I gave him a couple moments to process his own thoughts. I then asked him, “Isn’t it most philosophically consistent to say that all humans should get human rights?”

“Yeah, I guess so,” he answered. Then he asked me, “So why are you here showing pictures of aborted fetuses?”

I knew that it was then a good time to make the case for human equality. “I’m here because throughout history, humans have been denied human rights and personhood for so many reasons. People have been lethally discriminated against because of their race, or gender, or their sexual orientation. Today, in Canada, an entire class of human beings are denied rights and personhood because of their age–because they’re living in the first 9 months of life.”

He looked at our photos of tiny aborted children and said, “Yeah—all the arguments go back to their age.”He was silent again and then said to me, “Well, if your goal was to get me thinking, you’ve definitely succeeded.”

He took a pamphlet, shook my hand, and thanked me for the conversation before continuing to his class.

-

Speaking from the Heart

Originally posted on March 28th, 2018 for the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform

I felt like I was hitting a wall in my conversation with Danny at the Abortion Awareness Project. We had looked at pictures of aborted children, and we had discussed human rights and the difficult circumstances surrounding pregnancy. He would agree with my reasoning, and he even told me, “You’re really good at getting your point across.” Despite that, he kept reverting to his pro-choice position. If he understood the logic of the pro-life position, why wasn’t he convinced by it?

When we expose the truth about abortion, we see countless people become pro-life, but we also meet many who react with anger, obstinance, or apathy. We know from experience that those reactions nearly always mask some hidden wound. How can we address those deeper heart issues that block someone from accepting the truth?

The answer to this question is both simple and challenging: seek to understand. We cannot address people’s true beliefs about abortion unless we seek to understand what they believe, and why they believe it. When we seek to understand people, their deeper beliefs and their past experiences will often rise to the surface. In order to get to that point, we need to ask good questions, and then listen well to the responses.

I realized that although I was communicating intellectual arguments to Danny, I was not doing enough to seek to understand his point of view. I needed to reroute the conversation through questions and listening. So, I asked him an open-ended question: “What was it that made you decide that pro-choice was the way to go?”

He revealed to me a tragic fact: his mother had had two abortions while she was living in great poverty. At that point, I set aside the intellectual arguments and listened. I told him how sorry I was that she had gone through such difficult things. I tried to ask him gentle questions about his mother’s situation and about how she was doing now. “I guess that that experience kind of shaped the way I think about abortion,” he said. Danny told me that his mother wouldn’t talk much about the abortions, but she had expressed regret for her lost children.

Now it was perfectly clear why Danny struggled to accept the pro-life position: it would mean admitting that his loved one had made a serious mistake. I wanted to communicate to him that rejecting abortion did not have to mean rejecting his mother. So, I asked more questions: “Danny, imagine for a moment that I get a phone call. Someone tells me that my mom has been involved in a drunk driving accident that killed someone–and she was the one who was drinking and driving. Do you think that I would hate my mom because of what she did?” “Well, you’d probably be angry,” he replied hesitantly. “Yeah, I think I would be angry if someone I loved did that,” I said. “But do you think I would hate her and call her a terrible person? Do you think I would abandon her?”

He was thoughtful as he answered. “No… I think you would try to be a part of her healing journey.”

“Yeah, absolutely,” I told him. “Don’t you think it could be the same with your mom? She was part of a decision that ended someone’s life, and it’s a decision that has hurt her deeply. Don’t you think, though, that you could be a part of her healing journey?”Danny agreed with me, and we continued to discuss the impact of abortion and what it did to children and mothers. I asked him, “Do you think your mother made the right choice? Or do you think that if she’d had more support, she could have carried to term?” He was thoughtful again and said, “I think we could have made it. I think she could have done it.” He was starting to understand that his mother had needed real support, not abortion. He even asked me, “What do we need to do to prevent abortion?”

After a long discussion about his mother, Danny and I started to go back into the intellectual arguments around abortion, such as questions about prenatal development. He again expressed that our arguments made a lot of sense. “Powerful pictures,” he told me as he stared at the abortion victim photography. “You’ve kind of changed my view a bit.”

As we wrapped up our conversation, Danny and I talked about some other social issues, and he told me that he was so discouraged by all the problems with the world. “I guess that I have less and less hope for humanity,” he said with a depressed look.

I silently prayed for the right question, and one came to me: “Is there anything that does give you hope—for yourself or for others?” His face brightened, and he immediately responded, “My daughter.” He told me that his daughter was the reason that he wanted to get a job, get an education, and be a better person. I couldn’t stop smiling as he told me about this little girl whom he loved so deeply.

It can be challenging and scary to have these “heart” conversations. Every person’s story is different, and there is no perfect script for us to memorize. We can, however, be voices of truth and compassion to the people in front of us. Through our gentle questions and our intent listening, we can show people the love and respect inherent to the pro-life message.

And for hurting people, that compassion can leave a real impact. As Danny left for class, his expression was hopeful again, and his last words to me were, “Awesome conversation. Awesome conversation.”

-

Watching the Culture Shift

Originally posted on April 11th, 2018 for the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform

It’s a cold but sunny morning in Toronto. We set up for “Choice” Chain at various street corners around Ryerson University. I’m excited because we are there for a full day of outreach, and because there are so many of us—around 20 people spread across campus, with signs ranging from 3 feet wide to 10 feet wide. Most of our signs show first-trimester abortion victims, some show first-trimester ultrasounds, and some show second-trimester abortion victims. I know that we will reach thousands of people with pictures, hundreds with pamphlets, and dozens with conversations.

“What do you think about abortion?” I ask a young woman walking by. She’s hesitant and says she doesn’t know what she thinks about it. She opens the pamphlet I have offered her. I gesture to the photo within of the aborted child and ask her, “Do you think it’s ever okay to do that to another human being?” She says no, that is never acceptable. She asks what we can do to stop abortion.

Another young man stops. He initially tells me that he’s not sure what he thinks, but after we look at the photos, he agrees that abortion is completely wrong. He says to me, “I didn’t want to see these pictures, but you’ve got to be as visual as possible.” He thanks us and leaves pro-life.

We set up at a new location. A student stops to ask me some questions. She has spoken with another volunteer at a previous “Choice” Chain—someone who had taken her through the human rights argument. She wants to know more about our position: what do we think about abortion in the case of rape? I tell her, “I think that sexual assault is a horrific crime–one of the worst things someone can do to another person. We are failing survivors by not giving them enough support. And anyone who does that kind of a crime needs to spend their life in prison.” She nods in firm agreement. I then say to her, “I also know that we live in a country where we don’t even give the death penalty to the guilty rapist. Is it fair to give the death penalty to the innocent child?” I gesture to the picture on my sign. She thinks about this and then says, “Your logic is perfect. There’s really no situation where it’s okay to kill a child, regardless of the circumstances of how they came into existence.” She then tells me that she is confused about when human life actually begins. We discuss fertilization and different developmental features, such as consciousness. She has to leave for class and tells me that she is “still hung up on when life begins” and needs to do more research on it. She thanks me and says that the conversation was “really constructive.” She has now seen abortion victim photography multiple times, has spoken to two volunteers, and she is journeying towards the pro-life viewpoint.

At another corner, I speak with a student who thinks that abortion is needed if a woman is living in poverty. We find common ground in agreeing that women in crisis need real support, and we talk about some of the concrete ways to offer that help, such as volunteering at pregnancy care centres. I then give her an analogy where a woman becomes poor not while pregnant, but while parenting a born child. I ask her, “If it wouldn’t be okay to kill a born child because her mom is living in poverty, why would it be okay to kill a child before birth for the same reason?” As we talk more and look at the pictures of aborted children, she agrees that abortion is never justified. She tells me, “I think you guys are doing a good thing here. Thank you for talking with me.”

Those are just some of the stories I have from that day. And I was just one of the many volunteers who talked to people and saw their views shift. Now add in all the people who didn’t even talk with us, but who saw our signs or accepted pamphlets.

We know how to change the culture.

When we make visible the victims of abortion, the pro-choice worldview immediately begins to crumble. I’ve heard it once said, “The phrase ‘my body, my choice’ rings hollow next to a photo of another human body brutalized by abortion.” When people see the pictures, they understand the violence of abortion. They change their minds.

And when we speak to people about respecting human rights—when we speak to them about killing problems rather than killing people—they get it. They realize that the pro-life worldview is scientifically accurate and ethically sound. They change their minds.

So, we will show the victims. And we will speak up for the victims. When we do this, we win. Over the course of one day, the pro-life consensus grew at Ryerson University, and I saw this growth with my own eyes.

It will take hard work and dedication to shift the views of our entire country. It’s not easy. But it is simple.

Will you join us?

-

Sperm, Egg, and Embryo: What’s the Difference?

Originally posted on February 22nd, 2018 for the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform

It was about -10° during a recent “Choice” Chain, and I didn’t expect anyone to want to talk with me in such weather. Yet, within 5 minutes, Morgan stopped by my sign, and this pro-choice student was eager to have a long conversation about abortion.

As we discussed human rights and the science of human development, Morgan told me that he didn’t think we could know when human life begins. He thought that instead, human life must exist on a kind of gradient. He asked me how a single-celled zygote was any different from a sperm cell or an egg cell. I asked him, “Could a sperm left alone in a man’s body, or an egg left alone in my body, ever develop into a toddler or teenager?” “No,” he replied. “So couldn’t we agree then,” I continued, “that human life can’t begin before fertilization? And if we look at any time in a human being’s life after fertilization, can’t we still trace her life back to beginning at that point?”

He thought about this, but then objected again: “But if you take it back just a bit further, you have a sperm and an egg — they just haven’t met each other yet. So why aren’t those just half a human?”

While his tone was somewhat joking, I decided to take his question seriously: “I actually think that there is a radical difference between sperm/egg and an embryo, because a change in structure isn’t the only change that happens at fertilization. It’s not just a process of ‘1 + 1 = 2’. If you’ll bear with me for a moment, I can explain why I think that.” He nodded in agreement and I could tell he was listening.

“When scientists classify cells and organisms,” I said, “they need to look at two things: cell composition and cell behaviour. Sperm and egg have, typically, 23 chromosomes. That’s only half the genetic material needed for a human being. At fertilization, though, there’s a change in composition: the human zygote now has 46 chromosomes, a complete genetic code. And I’m sure you know about all the recombination that takes place at that time as well.” He nodded in agreement.

“There’s also a radical change in cell behaviour at fertilization,” I continued. “The behaviour of a sperm is to penetrate, and the behaviour of an egg is to be penetrated. But when sperm and egg fuse at fertilization, the new zygote doesn’t do those things. Instead, she grows and develops so that she can go through all the stages that a human being is supposed to go through. Those radical changes in cell composition and cell behaviour mark the change from gamete to organism.” (If I had remembered my apologetics better, I might have added in that the zygote has coordinated function, and self-directs her own growth.)

To prevent my explanation from sounding too much like jargon, I added in: “And you and I know this intuitively! A woman has eggs in her body, but she can’t get pregnant unless an egg is fertilized by sperm.” He again nodded in agreement.

Morgan had no response to my reasoning, and after that, he no longer presented any arguments that a human embryo was scientifically equivalent to a sperm or egg. He instead shifted his arguments back to philosophy, and argued that the embryo wasn’t deserving of human rights because she differed from us in so many ways. Nevertheless, our conversation was now grounded in the biological reality that human life begins at fertilization.

I don’t always delve that deeply into embryology with the person I’m talking to–especially if I think that I may lose their attention and interest. I brought up cell composition and behaviour with Morgan because I could tell that he had the patience for a long conversation. He had brought up many flowery philosophical terms in our conversation, so I decided that sharing more advanced information with him would show him the credibility of the pro-life perspective.

Over the course of 45 minutes, I found that Morgan’s pro-choice beliefs were deeply embedded in his utilitarian worldview and in his experiences of people close to him having abortions. Nevertheless, at the end of our conversation, he said that we had “scientific reasons” and “good arguments” to back up the pro-life position. He told me that he was going to keep thinking about the issue because it was so important, and he thanked me for having a respectful discussion with him.

I know that Morgan will need to reconsider many more aspects of his worldview before being able to accept the truth about abortion. I also know that the truth he heard and saw will leave “pebbles in his shoe.” Sharing the truth with people is always worth it—even if I sometimes can’t feel my fingers at the end of those winter “Choice” Chains.