-

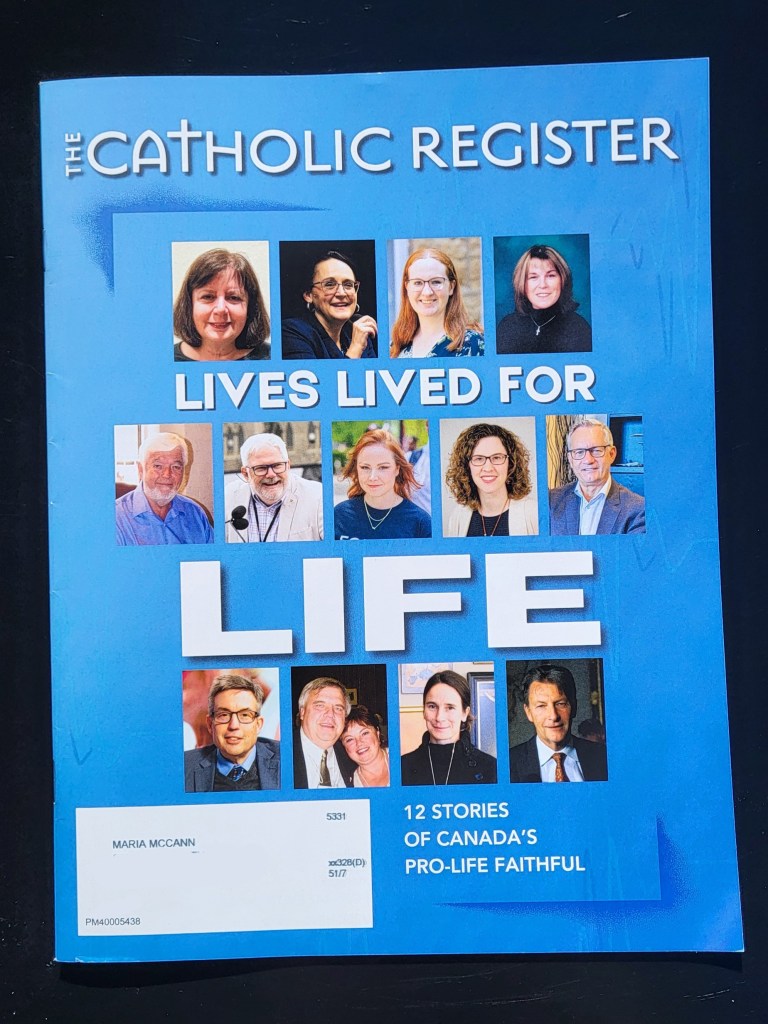

“Lives Lived For Life” Magazine

Earlier this year, I was interviewed by the Catholic Register about my involvement in the pro-life movement. I was overwhelmed and humbled to be included in their “Lives Lived For Life” issue, a special edition which highlighted 12 stories of pro-life Canadians.

My prayer is that anyone who reads the issue realizes that every one of us has a role to play in ending abortion. The pro-life movement is not about me or about you. It’s about our pre-born neighbours, little girls and boys, whom God calls us to protect from slaughter.

Get Involved: EndTheKilling.ca/TakeAction

I’m so grateful for the support of my family in doing this work, and for the countless pro-life colleagues who’ve become a second family.

Soli Deo honor et gloria!

-

What about Suffering?

Originally posted on November 10th, 2017 on the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform

In late October, I was doing a campus “Choice” Chain with my local community group. I asked a student named Arjun what he thought about abortion, and he told me that he was pro-choice. “Where I come from in India, there are a lot of children who are homeless and living on the street,” he told me with a troubled look. “Sometimes I think, wouldn’t abortion have been better? But maybe things aren’t as bad here in Canada.” Arjun’s response and his demeanour told me something: he wasn’t pro-choice because of a lack of compassion. He was pro-choice because of misguided compassion. I needed to show him both the humanity of pre-born children, and the inhumane nature of abortion as a response to suffering.

First, I found common ground with him–something I try to do in every conversation, to show the other person that I am listening to them. “It sounds like you care a lot about people who suffer,” I said. “Things may be somewhat better in Canada, but here in London, there are still a lot of homeless people, right?” He nodded in agreement. I then asked him, “Do you ever think, though, that we should solve homelessness by killing all the homeless people, since they are suffering?” “No, that wouldn’t be okay,” he said. “So if we wouldn’t kill born people because of their suffering,” I followed up, “then why would we kill a pre-born child just because she may suffer?” At that point, I gestured down at my sign showing an 11-week-old abortion victim. His eyes went wide as he took in the image, and he said, “I’ve never thought about this.”

We then talked about human rights, and about what abortion did to children like the one pictured on my sign. While he was stunned by the image, he pointed out that killing the pre-born child was perhaps less painful than killing a born child, so wouldn’t abortion be okay? “I think you’re right that a very early embryo probably doesn’t feel pain,” I told him. “But I don’t think that pain alone makes killing wrong. I think it makes killing more wrong, because then it’s like torture.” I challenged him with a question: “Would it be okay, though, to kill born children who are homeless and suffering, as long as we give them anaesthetic first?” “No, definitely not,” he said. He continued to study the image of the dead child in front of him, and I could tell that his horror at abortion was growing. I needed to show him just a bit more that abortion was never a solution to suffering and social problems.

“One of my friends told me an interesting analogy,” I said to him. “Think about an orphanage for a second. The children in an orphanage might not all get adopted and have happy lives, right?” He agreed. “Now imagine,” I said, “that someone decides to light the orphanage on fire with the kids inside. Would our first response be to line up adoptive parents for all the kids? Is that what we’d do while the fire is burning?” “No,” he replied, “we’d save the kids.” “I’m sure you can see where I’m going with this,” I followed up. “Making sure that children have good parents and social support is really important–but it’s not much good to those kids if they’re already dead. First, we need to save the children.” He nodded in understanding. I pointed down at my sign again to drive home the reality of abortion’s violence. “And Arjun, abortion isn’t even like not being able to save kids from the fire. Abortion is like pushing the kids into the fire on purpose.”

We talked a bit more and I asked him some questions about how he was finding life in Canada. Before he left, I said to him, “Arjun, after everything we’ve talked about, do you think there’s any time when abortion is okay?” “I’d never thought about it before this conversation,” he replied. “Now I think it’s an evil thing. You guys are doing a good thing here.” We shook hands, and he left completely pro-life.

By finding common ground, using analogies, and asking good questions, we can show people like Arjun that the violence of abortion is never the right solution to human suffering. We can show them that alleviating suffering is far better than eliminating sufferers.

-

Outreach Testimonies: Using the Human Rights Argument

Originally posted on October 13th, 2017 for the Canadian Center for Bio-Ethical Reform

I was doing “Choice” Chain earlier this month with some friends through my community’s activism group, London Against Abortion. We had set up outside of one of the colleges in London to reach post-secondary students with the truth about abortion. While some college students are hostile and closed-off to discussion, many will admit that they actually have not given much thought to the issue of abortion.

Such was the case when I asked Camille, “What do you think about abortion?” as she walked by me. She stopped and was taken aback by my sign showing a 1st-trimester abortion victim, but told me that she did not know what she thought about the issue. I then asked her, “Do you believe in human rights?” She said, “Of course I do.” “Great, me too!” I replied. “And who gets human rights?” “Well, women should,” she told me hesitantly. I replied, “I agree that women should—men should as well though, right? Shouldn’t every human get human rights?” She nodded in agreement.“If two humans reproduce, what species will their offspring be?” I asked her. She told me that she was not sure what I meant, so I clarified by saying, “Well, two humans could never produce a cat, right? Won’t their offspring be of the same species—human?” She agreed again. “And if that offspring is growing,” I said, “then wouldn’t she be alive?” She nodded, and I said, “I’m sure you can see where I’m going with this. If we know from science that humans reproduce other living humans, and if abortion intentionally kills those humans, then wouldn’t abortion be a human rights violation?” At that point I drew her gaze to the image of a 10-week abortion victim in the pamphlet she was holding. She stared at the image in shock and said, “Yes, it would.” I then asked her if she thought there was ever a time when it was okay to do that to another human, and she said, “Definitely not.” We then briefly discussed the magnitude of the abortion issue, and she ended up giving me her contact info so she could get involved in ending the killing.

Those questions that I asked Camille together constitute what we call the Human Rights Argument. Every human deserves fundamental human rights. We know that pre-born children are human because they have human parents, and we know that they are alive by virtue of their growth. Abortion is a human rights violation, since it destroys a living human being.

The human rights argument is a powerful tool that I use in nearly every conversation I have about abortion. It quickly establishes the humanity of pre-born children and the inhumanity of abortion, and for many people it helps them connect the dots to understand why they are horrified by the abortion victim image in front of them. For some conversations, it is the launching point from which I and the other person have a longer discussion about embryology, or bodily autonomy, etc. But for many people—including Camille—the human rights argument, combined with the visual evidence of abortion victim photography, is sufficient to convince them to reject abortion.

-

Truth and Healing

Originally posted on October 31, 2017 for the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform.

I’m standing on a street corner in Toronto, holding a sign with an image of a first-trimester abortion victim on it. Many passers-by tend to avoid my gaze and the pamphlets in my outstretched hand. A few pause to vent about why my colleagues and I are atrocious human beings who should have been aborted. A man stops in front of one of my shortest colleagues, but not to talk. He spits. She’s an easy target. It covers her face, her hair, even her arm. My eyes go wide, I fumble for my phone to film, but he’s already passed on. I rush over to help her.

I’m standing on the exact same street corner, probably even holding the same sign, more than a month later. I ask an older woman what she thinks about abortion. “I had one years ago,” she tells me quietly. “I regret it to this day.” I try to stammer out some words of sympathy and support, but she crosses the street. Out of my reach. Around 20 minutes later, she crosses back to my corner and stops in front of my sign again. “There was no one doing this when I had mine,” she says to me. “Thank you for being here.”

No one had been there to share the truth about abortion with her when she needed it.

I’m sitting in a coffee shop in London a week later. I’m trying to keep my mind off the abortion debate, and on the task at hand: preparing a presentation for one of my classes. I forget that the bold “EndTheKilling.ca” sticker on my laptop makes me an easy target for questions. The man in the booth across from me asks, “What killing? Is it about the seal-hunt?” I’m momentarily confused, then realize what he’s asking about. “No, not about the seal-hunt. It’s about the killing of pre-born children,” I tell him. “Ah, abortion,” he says, and I nod. “Yeah, you can find more information on the website if you’re interested.” I smile, and try to return my focus to my work.

A couple minutes later, he gets up from his booth, and says, “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have asked.” I glance up and see the tears in his eyes, hear the choke in his voice. “We lost a child—and—I shouldn’t have asked.” He’s about to go out the door. Out of my reach. I hastily say, “I’d be happy to have a conversation if you have a minute.” He stops, I get up, and ask him more about the situation. It was decades ago, he tells me. They got pregnant and they weren’t ready. She didn’t want to embarrass her family. So they got rid of the problem… “It only dawned on me recently,” he tells me through tears, “that it was a person.” I ask some questions about their situation, offer words of sympathy and support, and tell him about the group Silent No More. We shake hands, exchange names, and then he has to leave.

We get so little time with people. So little time to speak truth, to show love, to share our message. But we must share the life-saving truth—with as many people as possible. That’s what the images do. Nothing communicates the truth about abortion as quickly or as effectively as abortion victim photography. No one can tell the story of the aborted pre-born child like she herself can.

When Pope Francis referred to the Armenian genocide as a genocide—when he called the evil what it was—he provoked outrage from political groups who found that statement very politically incorrect. He refused to shy away from the truth and instead stressed the need to share it: “Concealing or denying evil is like allowing a wound to keep bleeding without bandaging it.”

The truth about an injustice can be so hard to accept. Our culture is so deeply wounded by abortion, and so desperate for healing. But no healing will begin unless it first takes place in the light of the truth. And no one will receive the truth unless we first have the courage to share it.

-

The call for an ethical conversion: seeing the faces of the pre-born

Originally posted on March 17, 2016 for the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform.

Several years ago, I encountered the ideas of the Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas while I idly skimmed my high school religion textbook. I was intrigued by his philosophy of “the face-to-face.” Levinas argues that when we encounter another human being face-to-face, we become ethically responsible towards that human being. He declares that “The approach to the face is the most basic mode of responsibility” towards “the Other.” I felt intuitively that his philosophy was true, but like most of my high school learning, his ideas fell into some cluttered filing cabinet at the back of my brain.

Levinas’ theory of the face-to-face came back to me in a surprising way two weeks ago, when I participated in CCBR’s Genocide Awareness Project. Under the guidance of CCBR’s incredible staff, I and my fellow participants visited two university campuses in Florida to speak with students about the injustice of abortion. We handed out thousands of pamphlets, had conversation after conversation, and wrote down testimony after testimony of moved hearts and changed minds. But our words were not the primary tool that engendered those effects on the campuses. Behind us, on large signs, were images of pre-born children who had been subjected to the violence of abortion. This abortion-victim photography showed the graphic and disturbing truth of what happens 3000 times a day in the US. When I asked students what they thought about abortion, those who said they were “pro-choice” often had a note of hesitation or embarrassment in their voice. The reason is simple enough: when we are faced with what choice we are talking about, the pro-choice label rings a bit hollow.

I remember one woman in particular who stopped by our display at FIU. The woman politely declined to speak with me, saying that she was “just there to look at the pictures.” I heard the horror in her voice when she said, “you can see their faces!” For many people like her, an encounter with the face of a murdered pre-born child stripped away every flimsy argument in support of abortion. However, not every student who saw our signs immediately voiced pro-life convictions. Some became angry, even belligerent. Though the students reacted in a variety of ways, I think that every kind of reaction can be explained through the lens of Levinas’ philosophy. In the book Ethics and Infinity, he states:

The first word of the face is ‘Thou shalt not kill’. It is an order. There is a commandment in the appearance of the face, as if a master spoke to me. However, at the same time, the face of the Other is destitute; it is the poor for whom I can do all and to whom I owe all. And me, whoever I may be, but as a “first person,” I am he who finds the resources to respond to the call.

If an encounter with the face causes a recognition of responsibility towards the Other, then an encounter with the face of the murdered pre-born child forces a realization: we have radically failed in that responsibility. We have failed that child. The primary “order” of the face, “Do not kill me!”, has been disregarded. The total vulnerability of the pre-born child, the one to whom we “owe all”, has been violently exploited. It is therefore very natural that people reacted with negative emotions: sorrow, horror, shock. Fury. Some desperately clung to their state of denial. But so many people that we talked to did accept the difficult truth. They agreed that abortion was a human rights violation, and agreed that we bear responsibility towards the pre-born. In my conversation with a student named Jack, he went from moderately pro-choice to completely pro-life after seeing the images and hearing our arguments. When I asked him if he thought that the pre-born needed protection, he declared that they need “the most protection” and that “silence is violence” on this issue. He saw their faces, and he took responsibility.

The faces of the pre-born do not merely convict us of the injustice of abortion and our failure in responsibility; their faces also call us to greater action in the future. Their faces call us to “do all” to end abortion, to save those to whom we “owe all.” I cannot phrase it better than Levinas himself: “The word of God speaks through the glory of the face and calls for an ethical conversion, or reversal, of our nature. What we call lay morality, that is, humanistic concern for our fellow human beings, already speaks the voice of God.” This ethical conversion, a rejection of selfishness, is desperately needed in our culture of death. Through the faces of the pre-born, God calls us to this conversion. How will we respond?

Ableism abortion adoption apologetics Audrey Assad beauty Bible biology bodily autonomy books Catholic Catholicism Christian christianity Christian poetry chronic pain CS Lewis culture disability euthanasia family God Inclusion John Milton literature London Ontario Love MAID ODSP philosophy Poetry Poets politics prescription pro-life pro-life speaker reflection RM Rilke Suicide Prevention Sylvia Plath Teresa of Avila theology TS Eliot value Viktor Frankl